06 Mar 2017

At the ISSI meeting I attended on quasi-periodic pulsations (QPP’s) in stellar flares in Switzerland in 2017-March, we had a great demo of the time-tagged photon data from GALEX by Scott Flemming & Rachel Osten, and the Python toolkit called gPhoton. This enables high time resolution (maybe 1sec) studies of stellar variability in the NUV (and FUV). Many projects came to mind from our group with this tool/dataset, including searching for QPP’s naturally.

Long-Term Variability

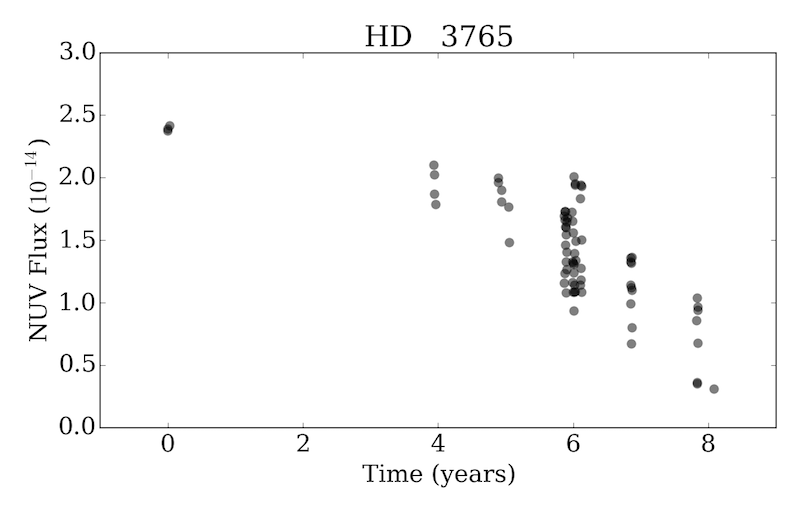

Some sources available with gPhoton have data from up to 10 years of repeated visits with GALEX! This caused me to wonder about the possibility of seeing long time-scale variability in the UV, which we might use to observe stellar activity cycles using GALEX! By using a list of Mt. Wilson H&K stars from Duncan et al. (1991), I wrote a quick Python script to ping the gPhoton database and count how many visits to each star were available.

Note: After corresponding with the gPhoton folks, it seems this may be a less efficient approach, and that an SQL-style database is also available for visit-level data that may suffice. Comparison of gPhoton with this coarser data is required!

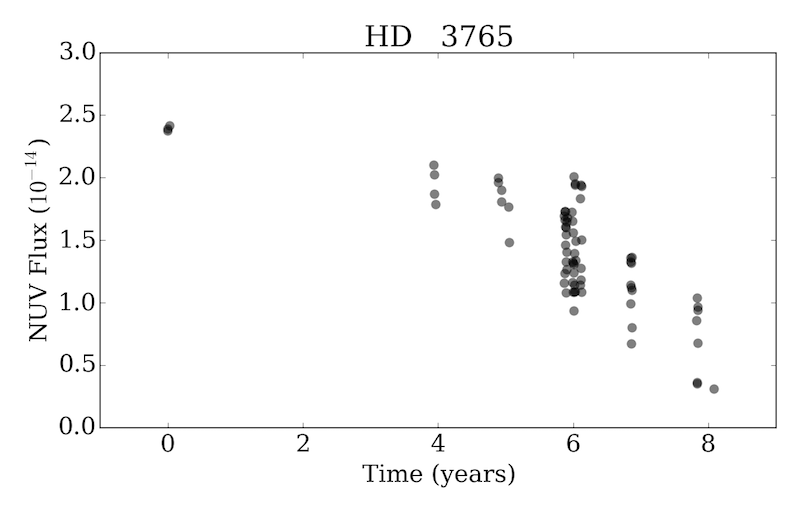

Here is the decade long light curve for one star, chosen to have the largest number of visits available (over 70). Each data point is the median flux value within the visit. The evolution is very interesting!

Next Steps

- Create a similar light curve for every Mt. Wilson (and other H&K survey) stars, looking for long-term variations.

- Compare the gPhoton with SQL-level data, to ensure variability is real

- Compare with the Gezari et al. (2013) catalog of variable GALEX sources

Python notebook on Github

Age-Activity

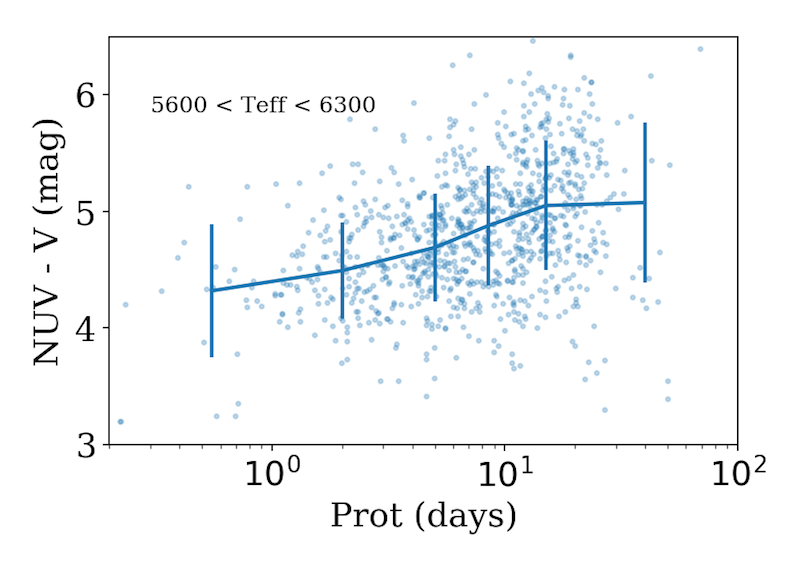

Following my recent exploration of rotation period distributions using Kepler & Gaia data, I was keen to see if the GALEX data showed any correlation between UV flux and stellar age. Activity levels traced versus stellar age with GALEX have been explored by Shkolnik & Barman (2014), using stars with known ages from clusters.

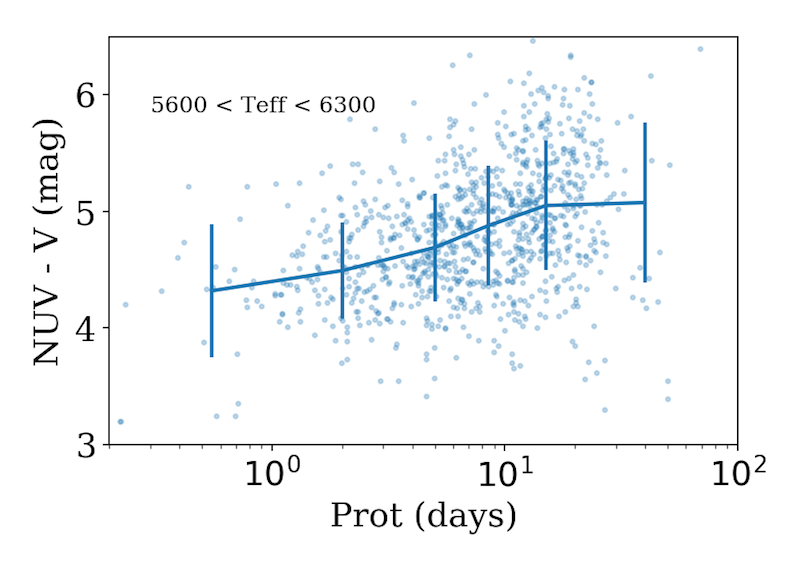

Instead of gPhoton, I used a dedicated dataset built from GALEX observations of the Kepler field by Olmedo et al. (2015). Using the excellent CDS X Match Service, I quickly and effortlessly matched this catalog to the McQuillan et al. (2014) rotation period dataset. To get more photometry, I then matched this combined catalog to SIMBAD with X Match. In a matter of 30 minutes from the airport I was able to get the data to make this figure:

For stars with a small range of temperatures, we can see the NUV flux appears to decrease compared to the V-band as a function of rotation period. Here I use the NUV-V color, as it is distance independent, and small bins in temperature to minimize the effect of different stars inhabiting different ranges of rotation period causing artificial spreads in the color. The evolution of less UV activity with increasing age (rotation period) is in the direction that is expected. However, the scatter is quite large.

Next Steps

- Improve sample selection with quality cuts for all data.

- Make similar plot for all available temperature bins

- Make plot as a function of Rossby number instead of rotation period

- Using a gyrochronology relation to infer rotation ages, plot the expected UV flux (or NUV-V color) from the fits of Shkolnik & Barman (2014) versus the GALEX data.

- Can we see a saturation regime with this data? If so, this dataset may be a valuable and large addition to the available sources!

- (Longer term) extend this sample with rotation periods from K2!

Python notebook on Github

25 Feb 2017

Background

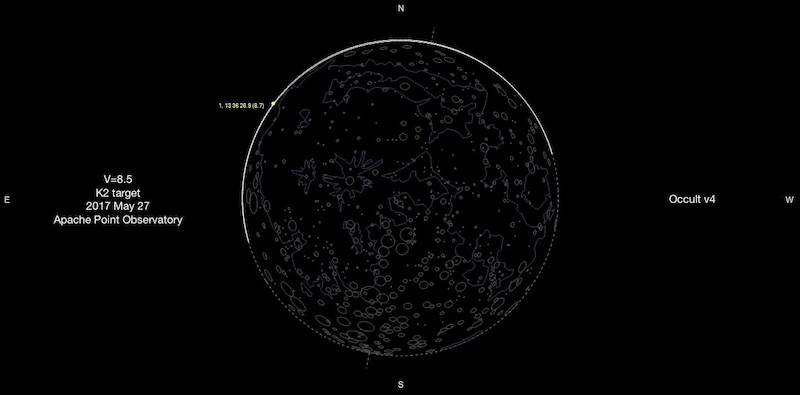

I had an epiphany in early 2016: The moon goes through the K2 fields. I mean, of course it does by construction. K2 has to point along the ecliptic due to using the solar wind as a 3rd axis stabilizer. The moon travels along ecliptic. In hindsight, it is very obvious.

This provides a unique opportunity: Lunar occultation studies of K2 targets.

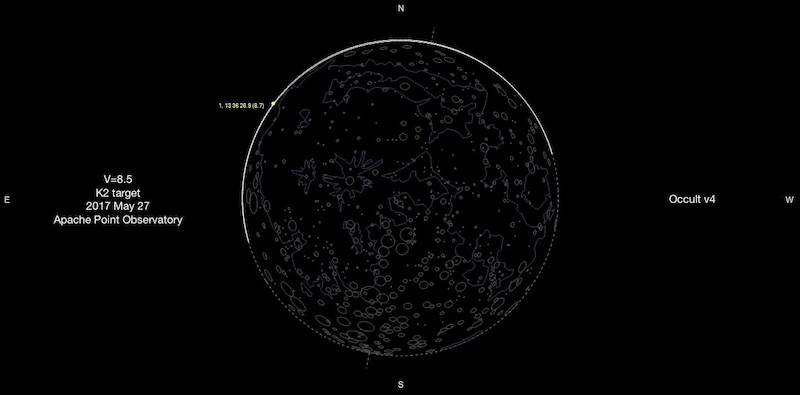

Such a project for community observers of occultations was described by the Occult software maker, Dave Herald, in this forum comment as an idea pitched by James Lloyd. The banner figure above is an example occultation in May 2017 of a K2 target observable from APO, as computed by Occult v4.2.0

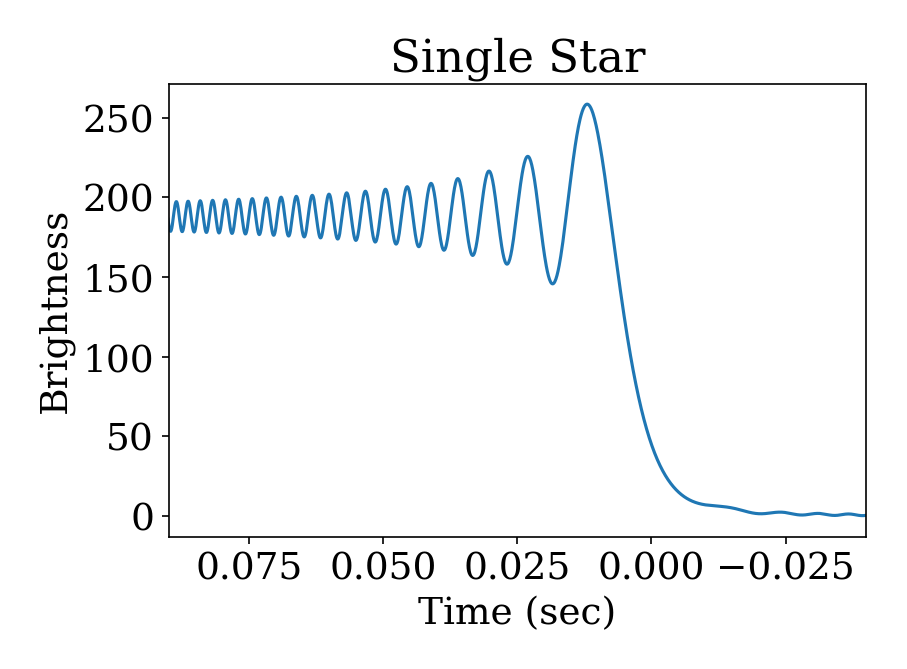

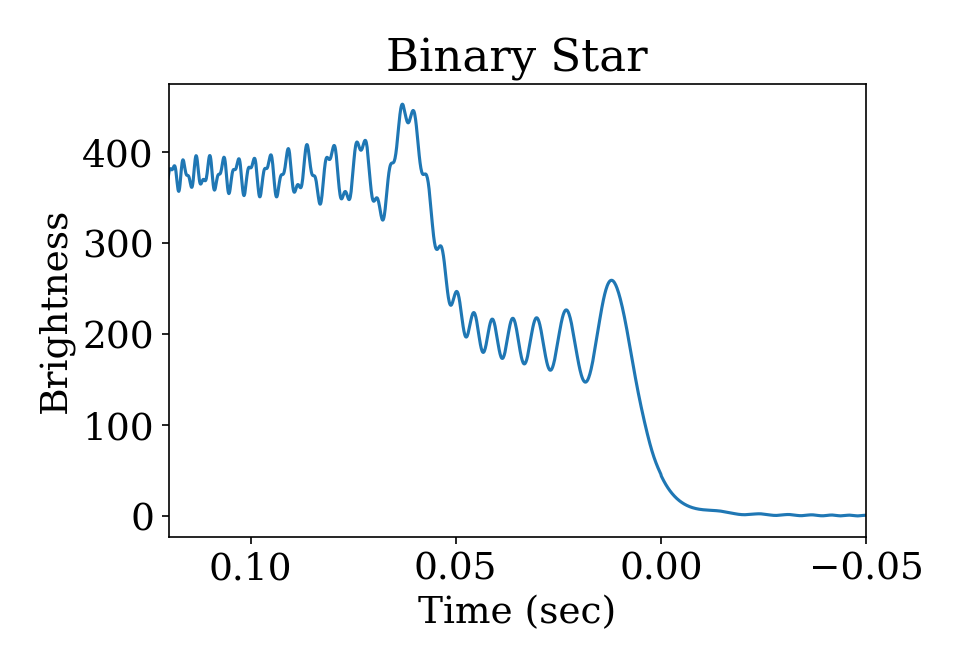

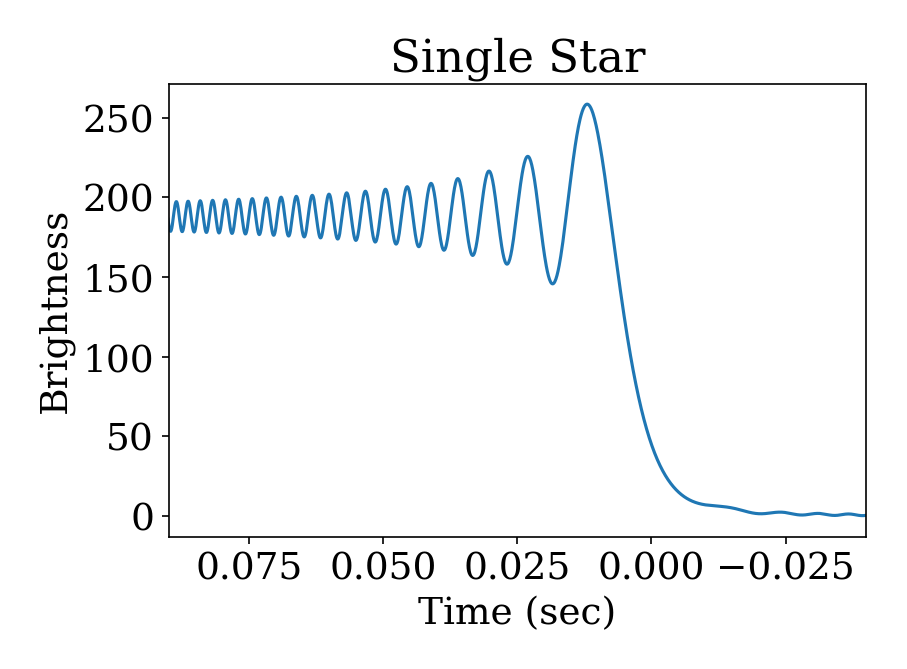

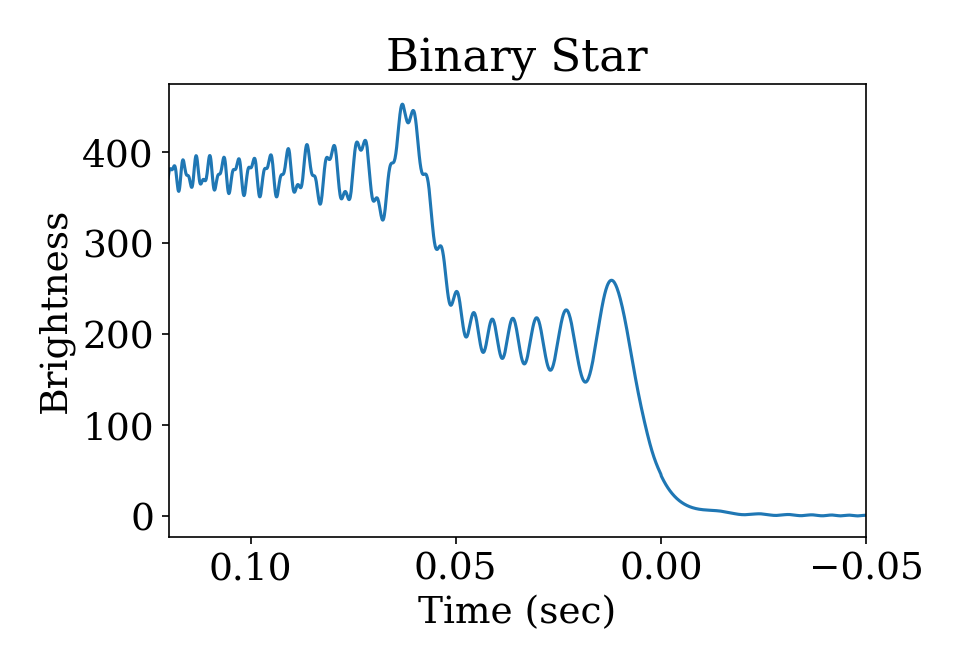

Lunar occultations can be used to estimate the angular diameter of background stars. It can also be used to determine if a star is actually a binary! Check out these toy examples I coded up:

Occultations allow binaries to be detected at milli-arcsecond separations, assuming the stars are separated along the direction of occultation, and can detect companions up to 11 mag fainter! This means occultations could even be used to detect exoplanets with next-generation large telescopes.

Here is a nice review of the methodology and technical considerations from 1994 by Richichi, where the author notes the field of occultations has been relatively stagnant for 20 years. Unfortunately more than 20 years hence, the same is largely true, and LO remain a fringe technique for stellar astronomers.

Challenges

The first and most obvious constraint to occultation work is the limited number of stars available for study. To wit, we only have 1 moon… though other Solar System body occultations of background stars are frequently observed (e.g. Saturn, asteroids, etc), and are good targets for JWST study - but these are for understanding the Solar System, not stars!

We are also put off by the need for very high speed imaging, often at infrared wavelengths. The events last only a few 100 ms at best, requiring an ultra-fast CCD or video camera system. The Signal-to-Noise requirements of 1-10ms exposures means that occultations are typically only possible for very bright stars, often V<8.

There are other considerations for observing wavelength and telescope diameter, as we are working to measure the diffraction of starlight by the lunar limb.

A Solution?

Fors et. al (2001) described an alternative approach to measuring occultations that particularly appeals to me: drift scanning. (First proposed by Sturmann in 1994) In this approach we read the CCD (camera chip) out at a rate that smears the starlight over many pixels. Since the CCD read is at a constant rate, the time evolution of the event is preserved, often at a resolution of a few ms. Note we are reading the camera while the shutter is open. This is basically the opposite of what SDSS did, where the CCD’s were read at the same rate the sky was drifting by, causing starlight to not smear as the charge moved along the chip, but gave continuous images of the sky. (brilliant!)

This drift-scan approach is attractive because it only requires an off-the-shelf CCD chip, and a little help from some adventurous engineers (e.g. the readout clock speed needs to be tuned, shutter needs to stay open, etc)

With access to lots of telescope time (actually very little time per object!), and minimal changes to a facility instrument, a survey of occultations for K2 sources should be undertaken! I can think of 1 or 2 medium aperture telescopes this would be ideal for…

Future

Drift spectroscopy? Could be possible with a longslit spectrograph (one way time resolved spectroscopy was done in olden days…)

24 Feb 2017

There are some awesome surveys of variability that are being under utilized. One such gem is OGLE, which now has a catalog of over 48k eclipsing binary star systems in the SMC and LMC!

With such a large sample, and near complete coverage of SMC/LMC (and in-between….) it would be amazing to see: are there variations of the eclipsing binary star population over an entire galaxy?

To do so, you might combine this variability survey with other spatial surveys that have traced the star formation history of the LMC/SMC… here’s a more recent paper on the subject.

We (or at least I) might naively expect that the orbital period distribution would be changed as a function of mean age of the stars in a spatial bin - in other words, dynamic processing would harden (shorten) the periods over time. Long period, detached systems would become more rare over time, and so also increasing the fraction of W UMa type systems.

Here’s a catalog with some updated fits to the light curves for the OGLE-III LMC systems.

Finally, working in the temporal-spatial domain is good practice for the forthcoming “LSST era”. As they say, publish early, publish often!

07 Jan 2016

TESS will take (and save) Full Frame Images at 30 minute cadence for their entire mission. However, like Kepler (and K2), the TESS pipeline will provide a differential photometry data product. i.e. the data is not flux calibrated.

The Guest-Investigator (GI) program for TESS does provide a level of funding for software projects if they are doing something value-added and unique for the community. Flux calibration should be very doable, given the FFI’s.

The question I see (and without enough knowledge of the TESS detector and hardware) is this:

What are the calibration frames that are required to do this?. Put another way, what could Kepler have done to accomplish this?

Some relevant literature:

15 Dec 2015

There’s a problem with making short period (like, 0.2 day) M dwarf binaries. They take too long to form starting from relatively close binaries (e.g. 2 day), like… a Hubble time to lose angular momentum. Yet, we see many systems like this.

Most people seem to care right now about how binary stars will affect planet evolution (e.g. ejecting planets from systems).

3rd body interactions have always been a popular culprit for forming such tight binaries. Galactic tidal influence might be able to do it too… but that’s usually thought about for wide binaries

So the idea:

Get best “Nbody model” (see my ignorance in its raw form!) of binary star system, with moderate separations (like, 1-10 days). Add a giant planet around 1 star. Run lots of simulations for 1 Gyr